This post is a little something different from my usual and is actually rather more like an old project of mine you can check out here.

This is an “experimental archaeology” project I did to present at the Costume Society of America symposium that was held this March in Williamsburg.

The project consists of historically accurately reproducing a mid-18th century nightgown (fitted back style) and then altering that same gown to c.1780.

Why do this you may ask? Well, I don’t know if I’ve mentioned it here before but I wrote a PhD thesis a few years ago all about the alteration and re-use of 18th century women’s garments. I’ve been itching to do a related reproduction project from that research for a while now and the CSA symposium finally gave me the chance I’d been waiting for!

Here’s a couple of snap shots of the finished exhibit, entitled:

‘1 Nightgown new made’: A Practical Investigation of Eighteenth-Century Clothing Alteration

I’m going to share this project over 3 blog posts so as to keep each a manageable size.

This post introduces the project and goes through the first phase.

Project Outline

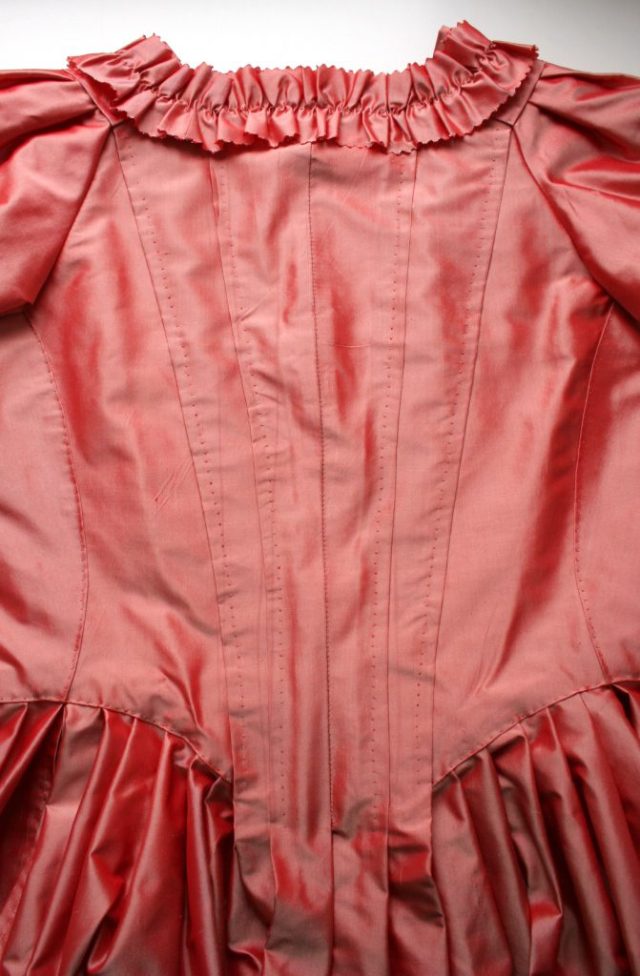

My project takes reproduction as a research methodology one level further by exploring the life of garments after initial construction via alteration. Alterations are ubiquitous among surviving garments of the eighteenth century, with one of the most common types being mid-century gowns re-made into fourth-quarter styles. To further my understanding of this process I undertook an “experimental archaeology” project of my own wherein I constructed a c. 1760 woman’s night gown (fitted back style) according to historical methods and techniques and then altered that same gown to a c1780 fashion style based on extensive observation and examination of such instances on surviving garments. This exhibition chronicles my experiences with the reproduction/alteration process and lays out my findings and conclusions.

I divided the project into 3 phases.

Phase 1:

- construct c. 1760 Nightgown and matching petticoat

- photo documentation

- identify areas and types of alterations to achieve a c. 1780 style

- formulate a list of steps to take

Phase 2:

- perform the alterations

- if applicable, amend the list of steps I formulated beforehand

Phase 3:

- photo documentation of the altered gown

- findings and analysis

Phase 1: 1760s gown and petticoat

Disclosure: I constructed this gown using the Nehelenia pattern as a starting point for pattern shapes but modified it and constructed it according to what I already know of construction in the period.

I don’t have a construction post for this gown as the focus of the project is the alteration process.

This first set of photos depict the 1760s gown on its own, to show just the gown style. However, I do have the appropriate foundation garments on underneath: stays and pocket hoops.

I then accessorized the gown to style it for the 1760s to create an overall fashionable appearance according to the aesthetics of that time.

(note: the cap, “ribbon” necklace, neckline tucker and sleeve ruffles were made according to the patterns and instructions in the American Duchess guide to 18th century sewing)

Areas to alter for a 1780s style:

Based on my examination of original, extant 18th century nightgowns that underwent updating from the mid-century to post-1775 I identified the main areas on the garment where alterations would need to be performed to create the later style.

I should point out that while I found a lot of commonalities between gowns altered in this way, for this reason, I never found two that exhibited all of the exact same alterations. I came to the conclusion that there was a repertoire of alterations (just like with original construction techniques and methods) from which seamstresses and customers drew according to personal preferences and what the original garment construction did or did not facilitate. This project is an amalgamation of some of the more common techniques I observed but also incorporates my own personal preferences in terms of style and sewing techniques.

Note: All photographs of extant garments were taken by me.

Narrow the back pleats on the bodice

Over the 1770s and 1780s “en fourreau” style gowns continued to be popular but the bodice back pleating increasingly narrowed. You can see this was done on the extant gown below by the still-visible crease marks from wider bodice back pleats:

Remove falling cuff and lengthen sleeve

During the last quarter of the 18th century the elbow-length sleeves that had dominated through most of the century gradually gave way to longer styles – 3/4, 7/8, and wrist-length – and they narrowed somewhat. While the shorter style did persist, longer sleeves were a hallmark of the 1780s. As part of stylistic alterations sleeves were lengthened in various ways, sometimes even just with straightforward piecing that may or may not have been subtly executed.

This example at the Gallery of Fashion, Platt Hall, in Manchester is particularly well-done. The joining seam is “hidden” within the striped fabric:

Although it was a treat to discover that the extra fabric for this piecing was probably harvested from the earlier falling cuffs, as evidenced by the scallop pinked edge right at the bottom of one sleeve:

But I digress. (that happens a lot when I get talking about my research)

Another common approach was to lengthen the sleeve by adding a cuff to the bottom. This also facilitated achieving the fashionable sleeve silhouette, which curved around the elbow. For this project I chose to reproduce the style of added-on cuff of the solid yellow gown shown above:

I love how not only is the original sleeve end still intact inside the newer cuff but that the circular fabric applique that once encased a lead weight, so common in sleeves with falling cuffs, is still present!

Remove neckline and robing trimming

Unpick and unfold robings to use for new bodice fronts

There are two main indicators that a gown has been altered from a stomacher-front style to a closed bodice front style: there are old fold marks on the fronts from unfolded robings; or the bodice fronts are pieced – it’s also common to find some combination of the two.

In the gown shown below there are crease marks on the bodice fronts that may be left from unfolded robings. there is piecing in the neckline corners that may be to fill in space created by doing this – bodices with folded robings (rather than applied ones) were typically slashed at this juncture so the robings could be free from the bodice to more smoothly lay over the shoulders.

Piece linen for new bodice front linings

Unpick the skirt, shift fullness towards the back, re-pleat with smaller knife pleats all facing towards centre back

The gown shown below is another example of a mid-century one altered in the 4th quarter of the century and note the small knife pleats facing towards the back of the bodice. However, I should point out that not all skirts were re-pleated alike. I have seen ones re-pleated with the tiny knife pleats characteristic of the late-century but still facing towards the sides of the body, the occasional box-pleating, and larger pleats facing towards the back. Also note the crease marks on either side of the narrow ‘en fourreau’ back pleats that may indicate they were altered from wider pleats.

Another giveaway that the skirt has been re-pleated is when pocket slits are left intact but are now at the side back of the body rather than the sides, as in the example below. Pocket slits that far back really aren’t going to be very useful so it seems highly unlikely this was their original position.

And that’s it for Phase 1. The next post will go through Phase 2: the alteration process.

Thank you so much for such a fascinating and informative post. I could read research like this forever! Is the fabric your gown is made of a lutestring from Burnley and Trowbridge? It photographs beautifully!

And thank you again for answering all my questions about the little vest from the Agreeable Tyrant exhibit. I really appreciate your spending time with me. I was so excited and nervous about it.

LikeLike

Guh I love this colour so much I want to punch something. Looking forward to the continuation of this gown!

LikeLike

What an interesting examination and investigation! Thanks for sharing this!

LikeLike

So interesting to read your post. Can’t wait for the next installments.

LikeLike

Very neat! I can’t wait to read the rest. Though I must admit I don’t think I could face doing this kind of project without, oh, a 25 year break before the refashion! 😂 (I’m reminded a bit of a prom dress from the late 60s/early 70s that was refashioned for my niece’s graduation a couple of years ago.)

LikeLike

Fascinating.

LikeLike

Fascinating post, looking forward to reading the next one.

LikeLike

By “night gown” do you mean “evening gown”? I read the title and thought you were re-making sleeping clothes!!

LikeLike

Hi there, that’s a great question! This is actually one of many quirks to 18th century clothing terminology, at least in English. The term “Nightgown” really refers to the fitted-back style of gown worn throughout much of the 18th century, whether for day or eveningwear – confusing, I know! The title of the project is actually a direct quote from an 18th century Englishwoman’s account book. Outside of England it was known as an ‘English’ gown since it was particularly associated with that country. When the french adopted it in the 4th quarter of the century they called it the ‘robe a l’anglaise’ – which name may be more familiar to you. However, the English weren’t going to call it either the English gown or anglaise, it was either Nightgown or just gown. I don’t really know the origin of the name but it seems to have emerged at least by the 1730s.

LikeLike